Back to Office of Policy Analysis and Policy Advisory Council main page

|

Columns DCWatch

Archives Elections Government and People Budget issues Organizations |

Council of the District of Columbia Office of Policy Analysis Vincent C. Gray, Chairman-At-Large

Council of the District of Columbia January 4, 2008 Education Reform in the District of Columbia:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Enrollment & FY 2008 Budget | DCPS | Charter Schools | Totals |

| Enrollment (as of October 5, 2007) | 50,270 | 22,220 | 72,490 |

| FY 2008 Budget Request | $1,054,346,000 | $320,366,000 | $1,374,712,000 |

| FY 2008 Local Funds (includes special purpose revenue) | $860,453,000 ($10,004,000 in special purpose revenue) |

N/A | $860,453,000 |

Table 1: Enrollment and FY 2008 Budget Requests

Many Councilmembers, throughout the scheduled hearings on PERAA, expressed grave concerns about DCPS, especially with their inability to bring about the necessary changes and reforms while being held accountable for a failing system. Councilmembers watched as standardized tests reflected significant academic failures district-wide and DCPS enrollment decreased. The newly approved PERAA will facilitate Council involvement, but more, it will require the Mayor to outline a clearly defined strategy for reform of this vast education system in order to solve systemic problems. This major reform initiative will require a true partnership between the executive and the legislative branches of government. The Council will be required to provide adequate oversight to ensure that the implemented measures are yielding the intended results.

This frustration exists not only in the District of Columbia. Nationally, elected officials have expressed frustration and discontent with their public education systems and have made decisions to alter the governance structures to facilitate decision-making. The Mayor and the Council have an opportunity and the authority to strategically shape and direct educational and administrative policy reforms. Nevertheless, it is important to recognize the limitations of mayoral control. The push for mayoral control reflects rising frustration and desperation over poor student achievement, crumbling buildings, bureaucratic wrangling among school officials, and revolving-door superintendents but it is not considered a panacea. Changes in governance do not address the basic reasons for poor performance.

Nonetheless, it has been reported that the Boston, Chicago, and New York school districts have improved test scores, avoided teacher strikes, and had longer-lasting superintendents since mayors took over.9 In addition, they have standardized their curricula, ended “social promotion” of kids who fall too far behind, opened new schools to give students more choice, and brought in millions of dollars in corporate donations. But education specialists continue to debate whether students actually get a better education under mayoral control, whether academic gains will be permanent, and how much credit mayors should get for the successes.

Kenneth Wong, a Brown University education professor, examined test scores of the 100 largest school districts from 1999 to 2003. He found that students in mayor-controlled school systems often perform better than those in other urban systems. Test scores in mayor-run districts are rising “significantly,” he says. However, Wong says in his study that “there is still a long way to go before (mayor-controlled) districts achieve acceptable levels of achievement.”10

Conversely, Frederick Hess of the American Enterprise Institute says his review of previous studies finds that it is “inconclusive” whether mayors can raise test scores more than elected school boards. He says that solid data on student achievement has not been collected long enough. Likewise, test scores in other cities with elected school boards, such as in Houston, have increased.11 These experiences imply the challenges leaders face when advocating school reform.

In PERAA, the Council mandated annual evaluations of DCPS in regards to business practices, human resources, academic plans, and student achievement. However, the first evaluation will not be available until late September 2008. Overall, it will be difficult to assess the success of education reform and the direct results of the mayoral takeover due to a lack of reliable data. While the Office of the State Superintendent of Education is currently constructing a state-wide longitudinal education data system, this project will not be able to provide data for several years on student demographics, student achievement, and other reform measures. Nevertheless, the Council will still have to provide oversight of public education.

A historical review of the District of Columbia’s educational system reveals several ongoing concerns. In response, numerous reforms and studies have been offered and some implemented in an effort to enhance the system. For example, in 1968, Congress enacted the “District of Columbia Elected Board of Education Act,” which vested control of the public schools in the Board of Education. From the aforementioned period to present, the city witnessed several changes in the Board’s position and composition. In 1971,a lawsuit was filed against the District of Columbia, which resulted in the Court ordering on May 25, 1971, that per-pupil expenditures on the elementary level should not deviate plus or minus five percent from the city-wide mean, and the Board of Education was further ordered to file annually with the Court sufficient information which would prove compliance with the Court order to equalize per-pupil expenditures. Additional litigation in 1971 had a major impact upon public education. In Mills v. Board of Education, the Board of Education, the Superintendent, the Mayor, and the District of Columbia were sued on behalf of seven children who had been identified as mentally retarded, emotionally disturbed, or having behavioral problems, and who had either been denied education opportunities or dismissed by the public schools. The Court found that the District government had failed to provide suitable, publicly-supported education for children with special needs and exceptional children; and second, the public school system had been suspending, expelling, excluding, reassigning, and transferring students in some cases from regular instruction without providing the students and their parents with due process, or the provision of a fair opportunity to object through the means of a hearing. Ruling in favor of the plaintiffs, the judge ordered a system of procedures to guarantee student rights and special educational placement hearings. The Court also directed the government to submit to the Court a comprehensive plan for the education of children with disabilities.12 DCPS is still struggling to implement changes to the special education program.

Governance change is not new to the District of Columbia. In February of 2000, the Council amended the Home Rule Charter to alter the composition of the Board of Education, decreasing the number of Board members from 11 to 9 and creating a hybrid board, where 5 members were elected and 4 were appointed by the Mayor. This provision will eventually sunset in 2009, when the State Board of Education will revert to an all-elected Board.

In February 2004, the former Mayor proposed a mayoral takeover in the “Omnibus Board of Education and D.C. Public Schools Restructuring Act of 2004.”13 His proposal would have elevated the Board of Education to the state level to serve as ultimate authority for setting and enforcing statewide policies while the State Education Officer would report directly to the Board of Education. Altered by the Council, the comprehensive school governance reform proposal was ultimately vetoed by the Mayor as it did not retain many of the proposed governance changes.

Nonetheless, one of the most promising advances occurred in 2006 with the adoption and implementation of new academic standards and the development and release of the Master Education Plan. The content standards and the corresponding standardized assessment, the District of Columbia Comprehensive Assessment System (DC-CAS), were modeled after the much-admired standards of Massachusetts. For science and social studies, in addition to Massachusetts, DCPS utilized and customized standards from California, Arizona, and Indiana, three other states with standards that are considered among the best in the country. Experts that reviewed the Master Education Plan found it to be an excellent formula for turning around the District’s failing system. However, according to data provided by DCPS the total cost of implementing all of the recommendations would be $82.6 million in FY 2007, $91.4 million in FY 2008, and $90.1 million in FY 2009.14 Seemingly, implementation of the Master Education Plan would require additional resources for effective implementation. It is not clear as to whether or not this projection has been factored into the FY 2008 budget and financial plan or that it will be factored in at a later time. Nonetheless, additional resources will be required to implement substantial education reform in the District of Columbia.

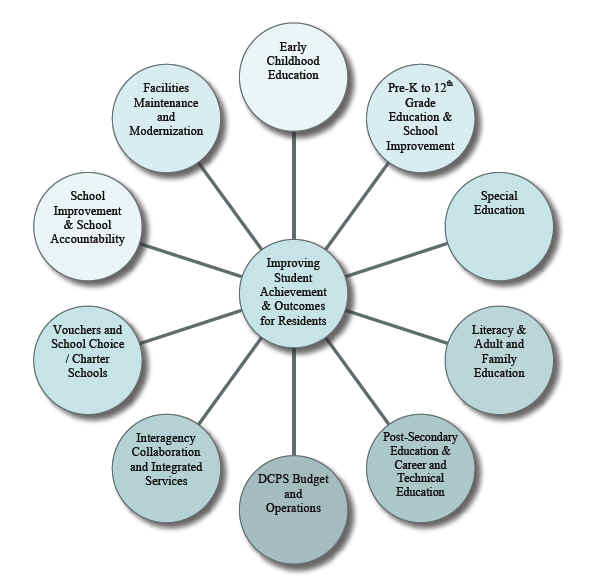

However, significant progress towards improving academic achievement and the outcomes of the residents of the District of Columbia will not occur until the school system resolves these longstanding issues.

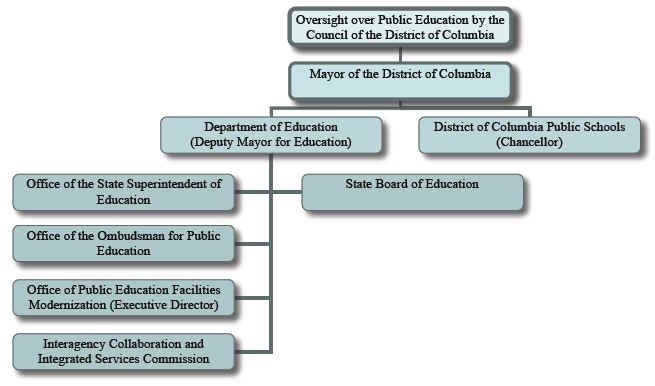

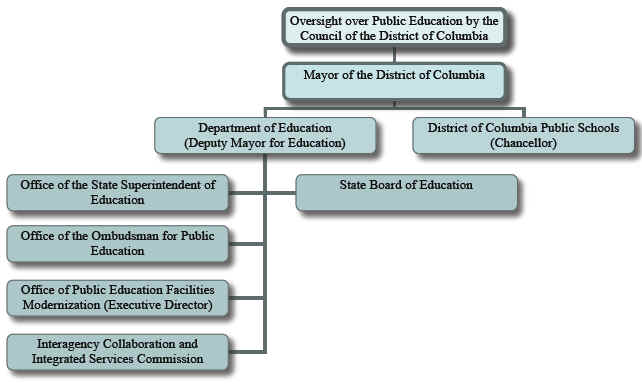

To implement school reform, PERAA established a Department of Education, led by a Deputy Mayor for Education (DME), tasked with various planning, promotion, coordination, and supervision duties, along with oversight of the Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE), the Office of Public Education Facilities Modernization (OPEFM), and the Office of the Ombudsman for Public Education. It also redesigned the State Education Office as the Office of the State Superintendent of Education, headed by a State Superintendent to “serve as the state education agency and perform the functions of a state education agency for the District of Columbia under applicable federal law, including grant-making, oversight, and state educational agency functions for standards, assessments, and federal accountability requirements for elementary and secondary education.”15 PERAA also created the Interagency Collaboration and Services Integration Commission to coordinate services of all youth-serving agencies, and ensuring implementation of best-practices programs; an Office of Ombudsman for Pubic Education to provide parents and residents an entity to which they can express their concerns and seek results; and the OPEFM to manage the modernization or new construction and maintenance of DCPS facilities. The Council must confirm the Deputy Mayor for Education, the State Superintendent of Education, the Executive Director of OPEFM, and the Chancellor of DCPS. The State Superintendent of Education is not subject to approval by the Council.

As previously referenced, Title I of PERAA stated that the Mayor shall promulgate rules and regulations governing DCPS, including rules governing the process by which the Mayor and DCPS seek and utilize public comment in the development of policy. This permits the Mayor to rewrite Title V, traditionally know as the “Board of Education Rules” or “Board Rules.” While the proposed rules are to be submitted to the Council for a 45-day review period, the Mayor has yet to promulgate and submit them to the Council. The Council may wish to prescribe a timeline or compel the Mayor to deliver the rules and regulations governing education in the interest of the residents of the District of Columbia to discover the means that the Mayor and the Chancellor will use to reform DCPS. The rules would be indicative of the Mayor’s intentions and how the Mayor will apply authority under the new governance structure.

The following is a list comprised of the express and inherent powers provided by PERAA to the Council. Several of these items are detailed further later in this document while deadlines and mandated reports have been summarized in the Appendix (See Tables 7 and 8).

(i) Business practices;

(ii) Human resources operations;

(iii) All academic plans; and

(iv) The annual achievements made as measured against the benchmarks submitted the previous year, including a detailed description of student achievements. (Express)

Accountability remains an important subject, influenced by the unique geopolitical structure of the District of Columbia. While PERAA authorizes DCPS as a cabinet-level, subordinate agency to the Mayor, DCPS is monitored by the Office of the State Superintendent, another executive agency. A substantial criticism of the former paradigm was that DCPS, as both a local education agency and a state education agency, was forced to monitor itself. However, under PERAA, the Mayor’s progress on education will be measured by another municipal agency. Only the Council remains as a completely independent body and therefore the Council has the responsibility of providing effective oversight.

The revised structure is further complicated with the addition of new education agencies and offices under the Mayor. While PERAA altered the governance structure, it did not greatly reduce the layers of bureaucracy overseeing the school system. The expanded bureaucracy may complicate, rather than simplify, decision-making as the roles and lines of authority and accountability are not clearly defined for all entities.

Figure 1 is a depiction of the revised governance structure.

Figure 1: Modified Public Education Governance Structure after PERAA 2007

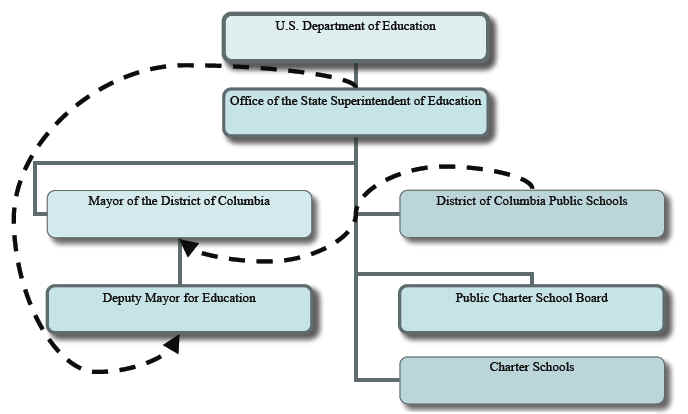

In this re-conceptualization, it is important to review the responsibilities of the Office of the State Superintendent of Education, especially in a federal context. Federal law, including the No Child Left Behind Act and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, requires states to monitor and report on a variety of different subject areas and performance measures within the local education agencies (i.e., DCPS and charter schools), including the submission of state accountability plans, reports of adequate yearly progress (standardized test scores), and teacher quality, among others.

The selected organizational structure may produce oversight issues, especially as management is dispersed among several separate entities. For example, while the Office of the State Superintendent of Education is required to report to the U.S. Department of Education, it remains an agency under the Mayor. Currently, DCPS, the entity that the Office of the State Superintendent of Education is monitoring for performance and compliance is also an agency under the Mayor, causing a potential conflict of interest and unclear lines of accountability.

Figure 2 demonstrates the complicated lines of authority and accountability.

Figure 2: Oversight and Monitoring Relationships after PERAA

Title I, Section 103(a) of the PERAA grants extensive powers to the Mayor of the District of Columbia stating that “the Mayor shall govern the public schools in the District of Columbia and shall have authority over all curricula, operations, functions, budget, personnel, labor negotiations and collective bargaining agreements, facilities, and other education-related matters.”17 The title grants all authority to the Mayor, relative to the District’s public education system; subsequent titles clearly outline the Mayor’s delegation of certain duties, responsibilities, and authority to the following departments, offices, boards, and commissions: the State Board of Education, the Chancellor, the Deputy Mayor for Education, the Department of Education, the Office of the State Superintendent of Education, the Interagency Collaboration and Services Integration Commission, the Office of the Ombudsman for Public Education, and the Office of Public Education Facilities Modernization.

In addition, all functions, authority, programs, positions, personnel, property, records, and unexpended balances of appropriations, allocations, and other funds available to the Board of Education, as the local education agency, established pursuant to Section 495 of the Home Rule Act for the purpose of providing educational services to residents of the District of Columbia were also transferred to the Mayor.

As the statutorily defined lawmaking body in the District of Columbia, the Council acts as a check and balance to the Mayor. While this may generate political tension, it may also lead to increased dialogue and collaboration. As this relationship matures regarding education, disagreements regarding education reform may dampen. Overall, increased oversight should lead to increased discussion between the executive and legislative branches, enhanced policy analysis and formulation, and effective implementation, ultimately creating better outcomes for students.A major challenge for the Council is the lack of measurable benchmarks to evaluate the transformation of public education in the District of Columbia. More importantly, the Mayor and Chancellor have chosen to share few of their priorities and their status with the Council. This could seriously undermine oversight efforts in the first year of implementation. Nonetheless, the Mayor released two reports earlier in the year, the “DCPS Reform Priorities of the Fenty Administration”18 and “An Action Plan for Special Education Reform in the District of Columbia.”19 The Mayor and Chancellor have also stated their intention to adhere to the Master Education Plan. These should provide a basic rubric to judge the implementation of school reform.

Informed by a myriad of sources, the documents list many goals and prescribe actions to achieve them. The draft report (a final report was never released) states activities, timeframes, and how each activity will be measured. The enumerated goals include:

Likewise, the special education reform plan, greatly modeled on previous work of the Board of Education, lists many issues, proposed actions, and a timeline. The enumerated issues include:

To date, the executive has not shared updates on these proposed benchmarks and academic plans; under PERAA, they will not be provided until September 2008. The Council’s oversight responsibilities would be greatly enhanced by regular updates on the progress in achieving policy priorities. This should also lead to increased communication between the executive and the Council. While oversight is typically practiced reactively, oversight is both a reactive and proactive activity. The Council may wish to be more proactive, by creating an oversight agenda and utilizing oversight as a means to improve programs and policy. Otherwise, the Mayor can set the agenda for education reform at the exclusion of the Council during the first year of implementation. This distinction will be discussed in the section entitled Setting the Agenda and Identifying Policy Priorities. Increased communication is necessary between the executive and the legislative to achieve coherent leadership on education.

The former Board of Education, while its composition has remained the same, has significantly different duties. It is now a State Board of Education and is removed from the local, day-to-day operation of the school system. Due to the unique geopolitical arrangement of the District of Columbia, there may be overlap of functions between the Council and the State Board of Education and the relationship between these two entities will need to evolve over time to establish delineations. The Council enhanced the Board of Education’s power and authority as originally proposed in Title IV, Section. Currently, the State Board of Education is both an advisory body and an explicit approval authority. This elevates the Board from purely advisory body as proposed to an actual policymaking entity.

As approved by the Council of the District of Columbia, the Board of Education has been granted final approval authority on a number of key academic matters. The Board could acquire additional duties and responsibilities, should either the Mayor elect to delegate additional authority to this entity or the Council enhances the Board’s powers by legislative act. Paragraph (b) of Section 103 provides that “the Mayor may delegate any of his authority to a designee as he or she determines is warranted for efficient and sound administration and to further the purpose of DCPS to educate all students enrolled within its schools or learning centers, consistent with District-wide standards of academic achievement.”22 This authority allows the Mayor to delegate any or all of his authority to an entity(s) that he may deem most appropriate to address the education policy, including the State Board of Education.

Pursuant to current District law, the State Board of Education has been granted both advisory and approval authority:

Advisory Authority

[To] advise the Office of the State Superintendent on education matters, including:

Approval Authority

It is important to note that when an entity has been granted approval authority, the approving body also, generally, inherently, possesses disapproval authority, unless such authority has been expressly prohibited. Further, if an approval authority rejects policy proposals and/or recommendations, such proposals and recommendations will not be implemented, unless the body’s inaction or disapproval can expressly be overridden. No such prohibition exists and no process to override the State Board of Education has been presented. How the Mayor defines the authority of the State Board of Education will be answered when the Office of the State Superintendent of Education formulates and promulgates rules necessary to carry out its functions, including rules governing the process of review and approval of state-level policies by the State Board of Education. This formulation and promulgation by the Office of the State Superintendent could restrict the authority of the Board substantially, relegating it to a de-facto advisory body, as was originally contemplated by the executive branch of government.

In addition, the Board shall conduct monthly meetings

to receive citizen input with respect to issues properly before it,

which may be conducted at various locations in each ward. Moreover,

the Board shall consider matters for approval upon submission of a

request for policy action by the State Superintendent of Education;

approval can proceed after a period of review. However,

it is important to note that the Mayor shall, by order,

specify the Board’s organizational structure, staff, budget,

operations, reimbursement of expenses policy, and other matters

affecting the Board’s functions.

Nonetheless, the Council is permitted to pursue legislative action under any of these categories, including the modification of content standards (e.g. urging standards of financial literacy) and high school graduation requirements (e.g. mandatory community service hours). Along with any legislative action taken by the Council that would affect the day-to-day operation of District’s education system, acting within this capacity moves the Council into a role akin to the former Board of Education. However, if the State Board of Education is successful in becoming a prominent voice for public education and is able to help set the policy agenda, the Council may find opportunities to legislate upon the advice and opinions of the State Board of Education.

The District’s model, relative to its Board of Education, is unique among reform models that have been selected and adopted by other cities around the country. From an overall perspective, reforms at the city level, including mayoral takeovers in Boston, Chicago, and New York City, were subject to the approval of the state legislature. In addition, each of the cities that have implemented significant reforms established local councils or bodies that address local education matters and issues. State academic standards are established at the state level, generally, by a State Department of Education. The District’s model is starkly different because the District has assigned state-level responsibilities to a locally based and locally elected entity, whereas all “local” educational matters, pursuant to current District law, shall be addressed through the District of Columbia Public School system and the Executive Office of the Mayor. This organizational design distinguishes the District from other reform models, yet its dissimilarity may be necessary due to the District’s unique geopolitical nature. Moving forward, it may be necessary for powers and responsibilities to be further modified to meet specific needs. A comparison of state K-12 governance Structures is shown in Table 3.

Pursuant to the legislation, the Office of the Ombudsman, which is an office within the Department of Education, will receive complaints and concerns from parents, students, teachers, and other District residents concerning public education, including personnel actions, policies, and procedures. The Ombudsman has the authority to determine the validity of any complaint and to examine and address valid complaints and concerns. According to the legislation, the Ombudsman shall also generate options for a response, and offer a recommendation among the options. It is not clear which entity will have the authority to officially resolve complaints. Formerly, the Board of Education assumed the role of advocate in public education; however, the Board met with resistance when asked to resolve complaints. Monitoring the Office of the Ombudsman is essential to ensure that the District’s bureaucracy does not interfere with problem resolution; if it does, the Council may wish to intervene and delineate additional powers to ensure swift solutions to problems as they arise.

Prior to the passage of PERAA, the Chief Executive Officer for DCPS as well as the Chief State Schools Officer was legally referred to as the Superintendent of Schools. The Superintendent, consistent with prior District law, was to be hired by the Board of Education and to serve as a non-voting member of the Board. The Superintendent, renamed the Chancellor under PERAA, was, and continues to be, responsible for the overall operations of the public school system. The Chancellor is to be appointed by the Mayor, with the advice and consent of the Council while the Chief State Schools Officer is now the State Superintendent within the Office of the State Superintendent of Education. The authority to hire or fire either of these individuals no longer resides with the Board of Education.

At the Chancellor’s confirmation hearing on July 2, 2007, many Councilmembers lamented that the Mayor did not follow PERAA’s prescribed selection procedures in selecting the Chancellor.23 Moving forward, it is important to ensure that all provisions of the law are adhered to and that the executive acts in accordance with the approved law.

Duties of the Chancellor

Duties of the Deputy Mayor for Education

In addition, the Deputy Mayor for Education will develop a comprehensive, District-wide data system that integrates and tracks data across education, justice, and human service agencies (the Interagency Collaboration and Service Integration Commission is responsible for developing the actual data system and ensuring that the data are current). The relationship between this duty and the ongoing efforts within OSSE to develop a state-wide longitudinal data warehouse is unclear.

Moreover, within 60 days of the effective date of the title, the Department of Education is required to report to the Mayor and the Council on the status of special education in the District of Columbia. The two reports mandated by PERAA include:

The Department of Education, as established in the District of Columbia, is very dissimilar to other state education departments. The statutorily assigned duties and responsibilities of the Office of the State Superintendent of Education are more consistent with state organizational structures that have been deemed state departments of education. The Council may wish to revisit the structure of the Department of Education and determine the feasibility of maintaining its current staffing levels or consolidating it with the Office of the State Superintendent of Education. Therefore, it may be constructive to examine the qualifications of the employees under the Deputy Mayor for Education against their roles and responsibilities.

The State Superintendent shall serve as the Chief State School Officer for the District of Columbia and shall represent the OSSE and the District of Columbia in all matters before the U.S. Department of Education and with other states and educational organizations.

All operational authority for state-level functions, except that delegated to the State Board of Education in Section 403 of PERAA, shall be vested in the Office of the State Superintendent of Education under the supervision of the State Superintendent of Education.

Duties of the State Superintendent

Transition Plan for Transfer of State-Level Functions

On September 10, 2007, the OSSE submitted to the Mayor a detailed transition plan for approval (in accordance with Section 7) for implementation of the transfers set forth in Title III. The transfer would begin within 30 days of approval; provided, that prior to completion and submission of the plan, the Mayor shall give notice of the contemplated action and an opportunity for a hearing for public comment on the plan which shall:

Transfer of Authority for State-Level Functions at DCPS

One of the most challenging and complicated areas in need of reform within the District of Columbia’s public education system is the provision of education services to individuals with disabilities and controlling the costs of the special education program. In the 2005-2006 school year, DCPS enrolled approximately 10,200 students in special education, almost 18% of their total enrollment according to the Master Education Plan. However, this 18% accounted for about 30% of total DCPS costs.24 Much of this disparity exists because 22% of those special education students were placed in non-public, residential, and interagency programs that require the District to provide transportation because school leaders or a hearing officer determined that DCPS could not meet their needs.

Recent testimony was provided to the Council concerning the costs associated with the District’s special education program and its impact on the overall operations budget for DCPS, e.g. the operations budget is affected annually when the budget for special education is insufficient. The need to allocate additional resources, during the academic year, to the special education program, impacts funding that has been approved and allocated for, as an example, classroom instruction, teacher aides, additional personnel, and guidance counselors. The Council of the Great City Schools found that the amount budgeted for special education in the District of Columbia is about 30% of the school district’s total current expenditure, compared with about 12.6% in the average urban school district.25 Studies indicate that there is an ongoing and long-term pattern of DCPS expending more on special education costs than is budgeted for that purpose. This pattern existed in FY 2006 and will likely be the same for FY 2007. Nonetheless, there was a reduction in the number of special education students placed in private schools in FY 2007. Improvements must be made if the District is to provide an adequate education to children with special needs.

Education officials have articulated that its emphasis will be on keeping District students that are classified as special education students in the District. The Deputy Mayor for Education noted that this would likely be the strategy of the current administration. He noted that there might be difficulties associated with addressing students that have already been placed in sites outside of the city. One method to reduce the cost of special education, as mentioned by the Master Education Plan, is to serve students in or near their neighborhood schools which eliminates tuition and transportation fees. This presumes that DCPS builds capacity, through the hiring of highly qualified special education teachers, and can develop a highly functioning student information system. Lastly, the “Interim Report of the Evaluation Team” regarding the Blackman-Jones consent decree stated that ENCORE, the current special education data management system, “is a cumbersome, illogical, inflexible system” and is inadequately and insufficiently maintained.26

In addition to the many challenges faced by the District of Columbia in delivering special education, the District has been involved in several lawsuits regarding the provision of services. Likewise, on April 21, 2006, the District of Columbia was designated a “high-risk grantee” by the U.S. Department of Education after failing to identify and correct non-compliance with the requirements of Part B of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), a federal law that guarantees children with disabilities the right to a “free and appropriate public education.” Specifically, DCPS failed to provide timely initial evaluations and reevaluations, to convene due process hearing decisions in a timely manner, and did not place students with disabilities in their “least restrictive environment.” Other areas of non-compliance dealt with monitoring to ensure compliance with the requirements of IDEA Part C relating to the early intervention services to infants and toddlers with disabilities and their families. PERAA moves the responsibility of meeting the District’s legal obligations and ensuring compliance with the Blackman-Jones (timely due process hearing decisions and timely service delivery) and Petties (timely payments to private providers and reforms in the DCPS transportation system for special needs students) consent orders from DCPS to the OSSE.

Another underperforming function being transferred to the OSSE from DCPS is the Office of Federal Grants. As state previously, the U.S. Department of Education designated the District of Columbia as a “high-risk grantee” for receiving federal funds. The Council may wish to conduct oversight of the Office of Federal Grants, now located within the OSSE, as they have been cited multiple times for long-standing problems of fiscal mismanagement, inadequate monitoring of grantees, inadequate management of information systems, and noncompliance with the federal Americans with Disabilities Act. The U.S. Department of Education also references other additional areas of noncompliance with program requirements found in their latest review. In addition, as the Board of Education previously approved the schedule for submission of program plans and grant applications, the Council may wish to request regular reporting of federal grants for monitoring as a means of providing oversight.27

PERAA authorized the transfer of federal grant compliance monitoring from DCPS to the OSSE. Having a strong state education agency will facilitate the Council’s work in helping promote high performing and high quality special education services and programs.

Transfer of Authority for the Board of Education

All positions, personnel, property, records, and unexpended balances of appropriations, allocations and other funds available or to be made available to the District of Columbia Board of Education that support state-level functions related to state education agency responsibilities and all powers, duties, and functions delegated to the Board of Education concerning the establishment, development, and institution of state-level functions related to state education agency responsibilities identified in Section 3 are transferred to the Office of the State Superintendent of Education.

Transfer of Authority for Adult Education Programs

All positions, personnel, property, records, and unexpended balances of appropriations, allocations, and other funds available or to be made available to the University of the District of Columbia that supports state-level functions related to adult education or adult literacy and all of the powers, duties, and functions delegated to the University of the District of Columbia concerning the establishment, development, and institution of state-level functions related to adult education or adult literacy are transferred to the OSSE. The OSSE is also authorized to establish fee rates for all adult education courses.

Transfer of Authority for Early Intervention Programs

All positions, personnel, property, records, and unexpended balances of appropriations, allocations, and other funds available or to be made available to the Department of Human Services that support functions related to the responsibilities of the Early Care and Education Administration and the Early Intervention Program and all of the powers, duties, and functions delegated to the Department of Human Services concerning the establishment, development, and institution of functions related to the Early Intervention Program are transferred to the OSSE.

The Council of the District of Columbia will have to exercise appropriate oversight to ensure that early childhood education and adult literacy continue to be top priorities of the OSSE. Nonetheless, as stated in the OSSE Transition Plan and observed at a Committee on Human Services hearing, disagreement remains on how and what components of the Department of Human Services’ Early Care and Education Administration will be transferred to the OSSE. According to the OSSE Transition Plan, this transfer will not occur until January 2008.28

An Ombudsman is serves as a “designated neutral” who advocates for a fair process and undertakes independent, fact-finding investigations in response to external or internal complaints or questions about performance. Traditionally, an ombudsman does not have the final authority or ability to resolve issues.

PERAA created the Office of the Ombudsman for Public Education to provide outreach to residents and parents and provide parents and residents an entity to which they can express their concerns about public education in the District of Columbia. The Ombudsman will recommend policy changes and strategies to improve the delivery of public education that may require legislative action by Council. In addition, the Ombudsman, via the Deputy Mayor for Education, will submit monthly reports to the Council that includes the content and nature of inquiries, complaints, concerns, examinations pending, and recommendations within 90 days of the end of each school year.

Duties of the Ombudsman for Public Education

The Mayor shall submit a nomination for Ombudsman to the Council for a 45-day review, excluding days of Council recess. If the Council does not approve or disapprove the nomination, by resolution, within this 45-day review period, the nomination shall be deemed approved.

If a vacancy in the position of Ombudsman occurs as a consequence of resignation, disability, death, or other reason other than expiration of term, the Mayor shall appoint a replacement to fill the unexpired term in the same manner as provided in subsection (a) of this section; provided, that the Mayor shall submit the nomination to the Council within 30 days after the occurrence of the vacancy.

Term and Qualifications

The Ombudsman shall serve for a term of three (3) years, may be reappointed, and must have the following qualifications:

Nonetheless, the subordinate role of the Ombudsman in the larger governance structure should cause concern. Since the Ombudsman is an executive entity and lacks independence, its neutrality will likely be questioned. Any issues requiring resolution will return to the Mayor or a subordinate executive agency for resolution, an inherent conflict of interest. In addition, reports are supplied to the Deputy Mayor for Education before reaching the Council, which is different from the OSSE and OPEFM who submit reports directly.

Several Councilmembers have shown an interest in creating “citizen education councils” to provide an unparalleled opportunity to gather community input and provide opportunities for greater citizen involvement. Citizen councils could provide not only guidance on specific issues and proposals, but vision and supplemental oversight pertaining to education. Citizen participation could greatly assist Councilmembers in oversight, agenda setting, policy formation, and decision-making. Previously, the Board of Education was empowered to create “neighborhood school councils” that would serve a similar purpose of informing members on issues that may require legislative action or oversight.29 There is a possibility that these entities may be viewed as serving similar, if not redundant functions to the Ombudsman. This may obscure the Ombudsman’s role; information gaps may emerge if an individual reports to a citizen council and not the Ombudsman, or vice versa. Therefore, a policy determination may be necessary for whether formal citizen councils should exist under the Ombudsman, with Council member participation, or chartered independently of the executive branch.

The Interagency Collaboration and Services Integration Commission is established to address the needs of at-risk children in the District of Columbia. As an established statutory goal, the Commission will focus on reducing juvenile and family violence and promoting social and emotional skills among children and youth through the oversight of a comprehensive integrated service delivery system. The Commission retains the authority to:

However, this section of the legislation is unclear from an operations and budgetary perspective. The legislation provides that the Commission may hire staff and obtain equipment, supplies, materials, and services necessary to carry out the functions of the Commission; however, the actual organizational structure and status of this entity is imprecise. Meanwhile, the fiscal impact statement accompanying PERAA specified only one full-time employee to be hired to staff the Commission. It is unknown whether or not the Commission has been properly staffed to execute its mission. Since the executive will be challenged to coordinate wraparound services for at-risk District residents, the ambiguous structure may hinder the Commission’s progress.

Nonetheless, the legislation requires the Commission, which is comprised of the Mayor, the Chairman of the Council, the Chair of the Committee on Human Services, the Presiding Judge, Family Court, Superior Court of the District of Columbia; the Deputy Mayor for Education; the City Administrator; the State Superintendent of Education; the Chancellor; the Chair of the Public Charter School Board, and relevant agency directors, to develop an information-sharing agreement within 90 days of the applicability of the title. Section 505 of the title permits the Commissions’ personnel to collect information from agencies participating in the agreement to facilitate comprehensive multi-disciplinary assessments and the development and implementation of integrated service plans.

The Commission is a critical design element of PERAA and offers a unique mechanism for achieving changes in how education, human, and social services are delivered in an integrated manner. However, PERAA is silent on how the Commission may recommend legislative action to the Council. In addition, a proactive Council may initiate, through the normal legislative process, remedies that would relegate the Commission to irrelevance. Nonetheless, the opportunity afforded the Mayor in breaking barriers to effective service delivery is great; effective oversight and participation will determine the success of Commission initiatives.

Title VII of the act establishes a new Office of Public Education Facilities Modernization (OPEFM). This entity is solely responsible for directing and managing the modernization or new construction of facilities within DCPS. Currently, modernization funding is in excess of $2.4 billion, which will support the largest modernization effort ever undertaken by the District of Columbia government. The Council will have to exercise detailed and extensive oversight of this effort as OPEFM has also been granted independent procurement and personnel authority.

The OPEFM is required to comply with the First Source Employment Agreement Act of 1984 and the requirements of the Small, Local, and Disadvantaged Business Enterprise Development and Assistance Act of 2005 (LSDBE). Oversight of compliance in these two critical areas is critical as well.

On October 2, 2007, the Council amended PERAA to transfer the duties of routine maintenance of school buildings and property from the DCPS Office of Facilities Management to the new OFM. Meanwhile, Allen Lew, the first Executive Director of OPEFM, has stated that the Master Facilities Plan, which outlines the timetable for school construction projects over 15 years, does not reflect the $75 million spent in Summer 2007 on repairs or upcoming maintenance, estimated to cost approximately $120 million. He has requested a year to study the plan, make changes, and hold community meetings to solicit feedback. At the October 2, 2007 legislative session, the Council addressed this request and amended the School Modernization Act of 2006 to provide that a revised Master Facilities Plan be submitted to the Council for approval by May 31, 2008. In addition, the Council required a work plan of activities and capital projects to be undertaken by the Office of Public Education Facilities Modernization in 2008 to be submitted to the Council within 60 days of the effective date of the Act (see Table 8).

However, at an oversight hearing on September 27, 2007, the Deputy Mayor for Education stated that he is planning to close several public schools before the 2008-2009 school year. As enrollment in DCPS declines and buildings become more expensive to maintain, OPEFM may recommend leasing, co-location, or the closing and disposition of school buildings. It was the sentiment of the Council that when the OPEFM submits the 2008 work program, it would prescribe a regimen of community input and community meetings. It serves public utility that excess space be used for other public purposes, such as health care facilities, public libraries, recreation facilities, or co-location with other agencies, including charter schools. Presumably, disposal of school property will have to undergo the same process as any other public property.

Notably, there has been concern about the funding of capital projects and oversight may be necessary; a forensic audit has already been recommended. Likewise, many reprogramming requests have emerged that withdraw money from the school modernization fund.

The Council should also be aware that the ability to enter into public/private development partnerships has been transferred to the OPEFM. Section 3514.1 of Title 5 in the DCMR, defines a public/private development partnership (PPDP) as “one in which an individual or organization, not affiliated with DCPS, partners with DCPS to utilize a DCPS controlled real estate asset in such a manner as to produce benefits to DCPS including . . . the provision of [other] goods and services which further the mission of DCPS.”30 Theoretically, PPDPs allow governments to achieve goals that the government alone could not adequately complete alone. Most PPDPs are sole-source endeavors.

Granted, the failed contract with EdBuild was a PPDP that the Council had very specific reservations about. In Ward 3, there is an ongoing discussion on whether DCPS should enter into a public/private development partnership with Roadside Development to build a residential unit on both the Tenley library and Janney Elementary School properties to earn revenue for both entities. The PPDP would build a new public library, put a residential building with fewer than 200 units adjacent to that library, build an underground parking garage to handle cars from both the new residents and visitors to the library, and build an addition to Janney Elementary School which sits behind the library building to relieve overcrowding. The community is divided regarding this new development. Unlike the previous governance structure, PPDP contracts will arrive at Council without review from the Board of Education.

Lastly, the Council has a role in ensuring that schools meet minimum construction requirements, therefore, in addition to meeting educational specifications, the Council may wish to enforce other standards, including “green” buildings or ensuring LEED certification.

School choice is a controversial issue in the District of Columbia, exacerbated by the poor performance of DCPS. Currently, the District of Columbia has a higher number of charter schools per student than any other state in America. Additionally, charter schools account for a quarter of the District's public school enrollment and should account for a majority of students by 2014 if these trends continue.31

PERAA authorized the PCSB as the sole chartering and monitoring entity in the District of Columbia. On or before July 30 of each year, the PCSB is required to submit to the Council an annual report on the PCSB’s chartering and monitoring activities. The Council should monitor the PCSB to ensure that charter schools meet their goals and that student achievement expectations are met. Enrollment in the District’s public schools has decreased significantly within the past five years while the number of charter schools has considerably increased as more residents elect to send their children to established charter schools. Meanwhile, there is no limit on the number of charter schools that may be opened in the District of Columbia. The District has an obligation to ensure that, regardless of the school selected, children have access to a top quality education. Consequently, the Council must work with the U.S. Congress to address the chartering of new schools. One possible reform consists of reconstitution of the PCSB as a District of Columbia entity under the Office of the State Superintendent of Education. Consequently, school choice may be worthy of review and may require revision, especially after the Mayor’s recent modifications to the funding formula.

Likewise, the D.C. Opportunity Scholarship program, a voucher program designed to send lowincome children in the District to purportedly better-performing private schools, has allowed some students to take classes in unsuitable learning environments and from teachers without bachelor's degrees, according to a Government Accountability Office (GAO) report.32 The GAO stated that the program lacks financial controls and has failed to check whether the participating schools were accredited. The $12.9 million program, in its fourth year, currently serves 1,900 students and provides funding to 58 participating private schools. The Council may desire to oversee the use of vouchers and the greater question of school choice in the District of Columbia and how it affects at-risk students.

Considering the Council’s immense responsibility to provide oversight over public education in the District of Columbia, several other policy areas immediately emerge. The following is a short review of pertinent policy areas subject to oversight by the Council of the District of Columbia.

Medicaid Recovery

The DCPS Medicaid Recovery Unit (MRU) generates federal reimbursement for health related services provided to the DCPS’ special education students enrolled in the District’s Medicaid program. This revenue helps to offset the cost of providing the health care and support services outlined in their Individualized Education Plan.33 However, in 2002, the District of Columbia Auditor found that the MRU did not properly and effectively manage the Medicaid recovery operations for DCPS because of a lack of sustained leadership, poor management, and inadequate staff and other resources.34 The Auditor prescribes many remedies that would increase the amount reimbursed to DCPS by several million dollars annually, including improvements in budgeting, staffing, and protocol for Medicaid billing.

To accomplish its mission, the MRU submits claims to the Department of Health’s Medical Assistance Administration (MAA) which administers the federal Medicaid program in the District of Columbia. Pending enactment, the authority of the MAA will be transferred to the new cabinet-level Department of Health Care Finance. The creation of this new department may aid Medicaid recovery reform efforts. The Council will need to continue exerting oversight over this critical area to ensure efficient funding for all DCPS students.

Likewise, increasing federal reimbursement for special education services would relieve other budget pressures at DCPS and would help offset the cost of providing the health care and support services outlined in their Individualized Education Plan.35 The Mayor and Chancellor have already asked the Council for additional funding to further enhance education reform, despite reassurances by the Mayor that education reform would be budget neutral. The Council should exert oversight over the multiple areas where cost savings can be achieved in order to reduce supplemental funding needs.

Personnel

Personnel issues after the enactment of PERAA may necessitate legislative action. On October 11, 2007, the Mayor of the District of Columbia submitted legislation to the Council of the District of Columbia that would amend the Comprehensive Merit Personnel Act of 1978 to reclassify non-union employees in the District of Columbia Public Schools’ central office as "at-will” employees serving at the discretion of the Chancellor.36 This legislation is part of an effort to give the Chancellor of District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS) the power to allow immediate separation of designated employees in a planned restructuring of the system's central administration. While most government and civil service jobs nationwide are not at-will positions, several jurisdictions have been experimenting with “radical civil service reform.” However, it is difficult to obtain an accurate picture of the extent to which at-will employment is expanding in the public sector, or to ascertain its potential as a growing trend. No broad-ranging studies have been conducted on the subject.37 The legislation also extends to OSSE and OPEFM. Currently, central office employees who are removed from a position have a contractual right to be placed in a lower-ranking position in the system while maintaining their salary. Supporters have stated that contract rights and due process has hampered previous superintendents who have sought in the past to downsize the school administration and remove poorly performing employees. The Council will be asked to assist the Chancellor in attempts to build a more robust central administration that is more receptive and responsive when dealing with parents, teachers, and principals. However, many questions need to be answered as to how this proposed legislation would impact the performance of employees or their willingness to remain as at-will employees.

The literature regarding civil service reform highlights an ongoing controversy over the employment-at-will doctrine and possible problems in implementing it. While reform of the central DCPS office may be necessary, how to achieve reform remains the current matter of discussion. It will be important to analyze political feasibility along with the equity, efficiency, and effectiveness of this measure. In addition, there is a risk of lawsuits or class-action suit from separated employees. Nonetheless, there are serious concerns with the expansion of at-will employment in the public sector that are generally not well understood. Moreover, very little attention has been given to the subject in public management literature. The problems are legal, managerial, and political in nature, and they bear directly on matters of public trust and institutional integrity, complicating the management of at-will employment relations.

A review of literature regarding civil service reform confirms that the pecuniary benefits of working in the public sector are meager compared to the private sector. According to Green, Forbis, Golden, Nelson, and Robinson,38 studies consistently indicate that public employees stay in the public sector because it offers relatively secure employment and other intrinsic inducements, such as challenging and rewarding work, the achievement of altruistic ideals, the desire to make a difference, the exercise of power toward that end, and participation in the policy process. In one case study of federal employees, the loss of job security, without change in compensation, caused morale to plummet and increased turnover comparable to the private sector.39 This likely caused a high loss of institutional memory and experience.

Nonetheless, at-will employment may better suit the next generation of workers who enter the workforce anticipating that their career path will involve a number of different jobs with different organizations. Younger workers no longer expect to form long-term psychological contracts with their employers; employees under 30 years of age tend to move from job to job, and this is facilitated by at-will employment. This epitome of freedom of contract is very attractive to young people and illustrates a possible generational trend that may be at play in support of at-will employment. While this may be positive for public sector managers who can attract and hire young, energetic employees, these employees likely have less experience and are more likely to leave, taking their institutional knowledge elsewhere. Likewise, it is less certain that when they get older, if they will strive for increased work protections. Lastly, as the agency moves towards a revolving door for younger employees, the cost of hiring and training employees becomes a larger budgetary constraint.

Another argument regarding at-will employment is that the shift to at-will employment sees markets as a solution to government inefficiency. However, governments are not markets. In fact, government exists because of market failure and because markets fail to serve the public interest and values such as equity, representation, and responsibility. This form of civil service reform minimizes the technical competence, social equity, and moral character in favor of partisan allegiance, loyalty, political responsiveness, and personal connections. However, the ascendancy of complex bureaucracies and a developed economy may prevent politicization of public sector employees. The size of state bureaucracies, which employ thousands of employees, and their sheer complexity, negates coordinated efforts to politicize entire bureaucracies. At-will employment may permit greater efficiency within a large agency.

It is arguable that changes in electoral politics may mitigate the looming problems of favoritism and politicization. Today, with the end of the spoils systems, votes no longer translate into jobs. Instead, interest group politics, lucrative government contracts, and the privatization of government functions fuel elections and electoral politics. Who gets what from government is no longer determined by the simple formula of votes for jobs; rather, it is a complex calculus involving contracts and large private interests. Hence, the move toward a “hollow state” with extensive privatization and outsourcing of governmental functions has diminished the importance of the individual government employee in electoral coalition building and enhanced the importance of satisfying large private organizational interests. As a consequence, jobs are no longer traded for votes on a large-scale basis, as they once were. While critics’ fears that at-will employment would bring a return to spoils once employee protections may not materialize, caution should be maintained towards excessive contracting and their negative costs.

Many arguments have been made about the ability of at-will employment to motivate employees. These arguments entail assumptions about what motivates people to work. Typically it is argued that public servants lack true accountability and enjoy too much job security and therefore, they should be subjected to competition for the work they perform. This argument assumes that public employees are lethargic and unresponsive; these theorists believe that civil servants must face the risks and uncertainties of private-sector employment to re-energize them. In this theory, civil service protections serve as a barrier to real productivity, efficiency, and responsiveness. This market approach to motivation assumes that people are driven primarily by economic incentives. This environment, perpetuated by a need to survive, is an environment where employees must compete or fail. Failure would conclude with the loss of employment. However, many studies demonstrate that financial incentives only play an important role in motivating employees when they are considering whether or not to take or leave a position, and ironically may even reduce workers’ motivation when tied to performance evaluations and merit reviews. Instead, intrinsic factors, such as the challenging nature of the work, career ladders, being appreciated, and good colleagues, bring far more job satisfaction in work life.40 These intrinsic factors are dependent on job security. Fear of losing one’s job may not motivate, but may adversely affect performance and the ability to maintain a stable workforce. In addition, this disproportionately focuses power on the manager under at-will employment; the employee must perform at the exclusion of the personal relationships that usually enhance productivity. This power may also inflate fear and distrust among subordinates. Even a manager’s mood may become an unduly stressful matter for employees. The impact of the manager’s words and actions becomes more acute, and this can easily retard or pervert organizational performance despite the best of intentions.

There are inherent difficulties in organizing a large at-will workforce. Top-performing employees may leave DCPS to seek employment in other organizations (for example, surrounding school districts) that are less risky and less politicized. The politicization of the DCPS central office also would permit increased opportunities for patronage from the executive branch as well as permit a new Chancellor to fire the entire central office staff. Past reorganization of the central administration has not lead to improvements.41 Lastly, extending atwill classification to teachers may have unintended consequences. Specifically, this may exacerbate the teacher shortage as teachers seek “safer” positions in surrounding jurisdictions. Likewise, it is difficult to reliably measure how a teacher is performing; a better solution may be a pay-for-performance plan.

Nonetheless, during the Council’s legislative session on December 18, 2007, a majority of the Council endorsed a modified version of the “Public Education Personnel Reform Amendment Act of 2007” after first reading.42 The revised legislation amended the District of Columbia Government Comprehensive Merit Personnel Act of 1978 to establish employment without tenure for DCPS central office employees, OSSE, and OPEFM. It will also require that the Mayor seek a voluntary separation incentive for certain DCPS employees and requires the Mayor to submit an evaluation of the personnel reform provisions of this act in September 2012.

The Council may wish to pursue alternatives such as advocating for performance management procedures, use of existing summary removal procedures, hastening the firing timeline, the temporary use of at-will employment, additional protections against wrongful termination, or enactment of other model personnel legislation (see the MODEL Employment Termination Act and Montana’s Wrongful Discharge from Employment Act).

It may also concern the Council that, according to the OSSE’s transition plan, 123 employees were transferred from DCPS to the OSSE, increasing the size of the OSSE from 85.5 employees to approximately 370 employees as of October 1, 2007.43 Nonetheless, it is difficult to compare the District’s state education agency to other states due to our unique geopolitical structure.

Additionally, the Council should exert continued oversight over executive pay in public education. Since DCPS is a subordinate agency under the Mayor, a consideration should be made as to whether DCPS salaries should be similar to executive salaries provided in other District agencies. Reportedly, the Chancellor has offered the deputy chancellor at DCPS and the chief of staff salaries that exceed the $152,686 cap for such supervisory positions.44 They will receive $200,000 while the Chancellor will receive $275,000 plus signing and performance bonuses. Chancellor Rhee has also offered six-figure salaries to several other staff members. According to District of Columbia Department of Human Resources, the pay range for government supervisors who are not appointed by the mayor is $56,740 to $152,686.45 The Council has already passed an emergency resolution to give the Mayor the authority to offer up to $279,900 a year for each of six positions, including the Chancellor’s, while a hearing on the “Executive Service Pay Schedule Emergency Act of 2007” occurred on September 26, 2007 that would increase the number of pay levels for executive service.46

Procurement (Textbooks, Supplies, etc.)

The District of Columbia Office of Contracting and Procurement has encountered significant problems that have lead to decreased transparency, accountability, and competition in procurement; many of these difficulties are duplicated within the DCPS Office of Contracts and Acquisitions (OCA). After PERAA, the Council will be able to extend oversight to the DCPS OCA which has failed in its mission to "consistent provide efficient and effective procurement” as well as timely service for DCPS.47 However, OCA may not be effective and may require restructuring and overhaul to improve the tracking and elimination of wasteful practices. This would ensure provision of the best possible services, products, and fair prices. DCPS has traditionally been challenged to effectively manage and oversee its procurement function and therefore, oversight may determine whether the DCPS procurement system incorporates best practices and accepted key principles for protecting taxpayer resources from fraud, waste, and abuse. Nonetheless, OPEFM and the interagency Commission also have independent procurement authority, which signifies a need of the Council to exert oversight for these entities as well, or a decision to integrate the independent procurement functions with the District of Columbia’s Office of Contracting and Procurement.

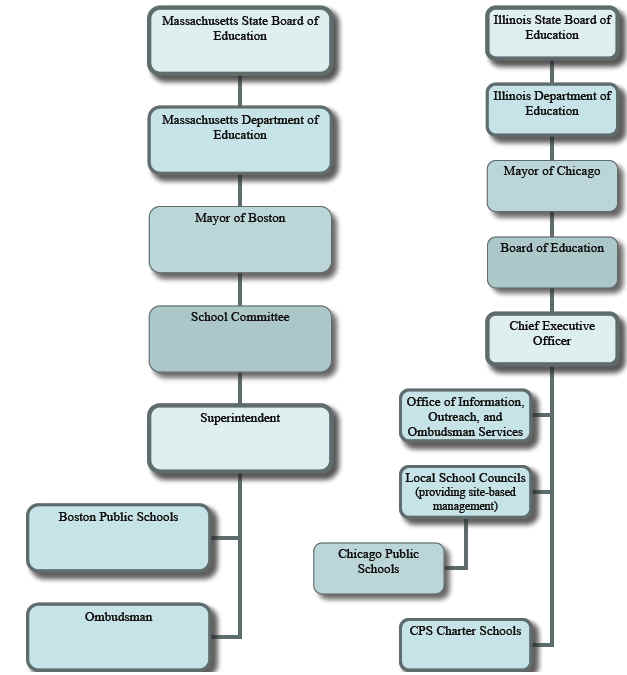

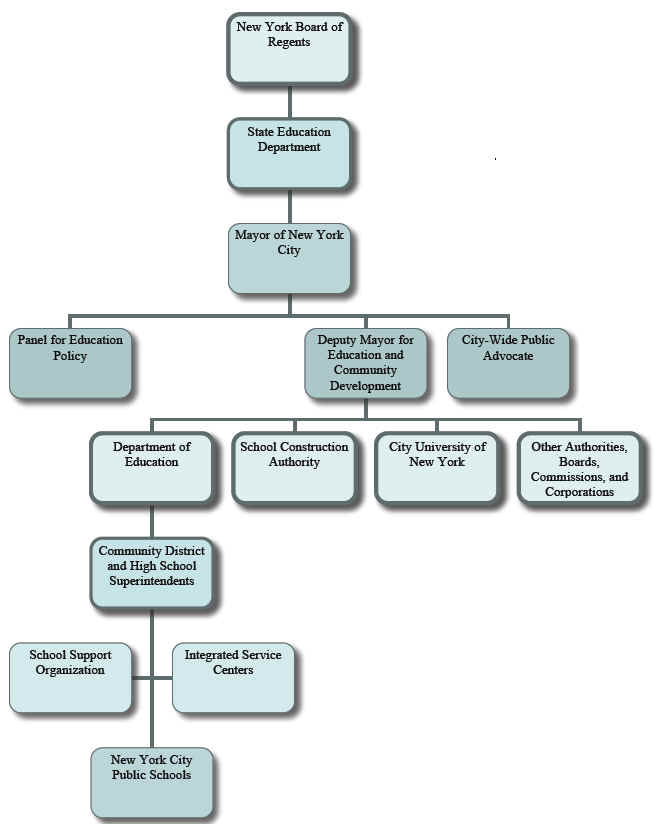

Like the District of Columbia, the public education systems in Boston, Chicago, and New York have undergone mayoral takeovers although the characteristics of each school district vary immensely. Of this small sample, Boston and the District of Columbia are of similar size and budget as compared to the massive Chicago and New York school districts.

| Characteristic | Boston, MA | Chicago, IL | New York, NY | Washington, DC |

| Population | 589,141 | 2,896,016 | 8,008,278 | 500,000+ |

| Student Enrollment | 57,000 | 420,982 | 1.1 Million | 50,270 |

| Annual Budget | $747,100,000 | $4.4 Billion | $15 Billion+ | $1.Billion+ |

| Number of Schools | 148 schools, 18 are pilot schools | 623, 27 are charter schools | 1,400+ | 167 schools and centers, |

| Total # of Employees | 9,133 | 44,417 | 130,000 | 8,329 |

Table 2: Selected Characteristics of Comparison Cities 48

The table below illustrates the state governance structure under which each takeover took place. Then, on the following pages, graphic representations of these cities’ local education systems are presented. Alongside the new governance structure of the District of Columbia, it should be immediately recognizable that each of these cities and their states has a separate, independent chief state schools officer and a state education agency.

| Governance Body | Boston, MA | Chicago, IL | New York, NY |

| State Legislature | The legislature has a joint education, arts and humanities | The legislature has a House appropriations – elementary and secondary education committee, a House elementary and secondary education committee, and a Senate education committee. |

The legislature appoints all of the members of the state board of education. The legislature has an an Assembly education committee, an assembly library and education technology committee and a Senate education committee. |

| Governor | The Governor appoints 7 of the 9 voting members of the State Board of Education. | The Governor appoints all of the voting members of the State Board of Education |

The Governor does not appoint any voting members of the State Board of Education or the Chief State School Officer. |

| Chief State School Officer | The Chief State School Officer is appointed by the State Board of Education. | The Chief State School Officer is appointed by the State Board of Education. | The Chief State School Officer is appointed by the State Board of Education. |

| State Board of Education | There are 9 voting members of the State Board of Education, 7 are appointed by the governor, 1 is a high school student elected by the state student advisory council, and 1 is the Chancellor of higher education, appointed by the Board of Higher Education. | The Governor appoints all 9 voting members of the state board of education. | There are 16 voting members of the state board of education. All of the voting members are appointed by the legislature. |

| Local School Boards | Mayor appoints all 7 School Committee members to four year terms. | Mayor appoints all 5 members of the local school board and the board president. | Five of the 13 members are appointed by the 5 borough presidents, 8 are appointed by the mayor and include the Chancellor who serves as chairperson. There are 32 community school district boards in the school district. |

| Local Superintendents | The Boston Public Schools Superintendent is appointed by the School Committee. | The Chicago Public Schools CEO is appointed by the Mayor of Chicago. | The Chancellor is appointed by the Mayor. The community school superintendents are appointed by the Chancellor. |

In their analysis of PERAA, the Council of the Great City Schools stated that DCPS has been beleaguered by multiple and intrusive governance layers and a poorly defined internal organizational structure. In most urban school systems, the internal structure and alignment of staff and functions are usually more important to efficiency and effectiveness than is the external governance and organizational structure.50

As stated earlier, the Boston, Chicago, and New York school districts, along with most other school districts nationwide, are monitored by a state education agency, a separate state-level entity. In the District of Columbia, our geopolitical situation spurs a unique development where both the state and local education agencies are under a single authority: the Mayor. Therefore, it becomes unclear how conflict of interest problems can be resolved.

Thus, accountability remains an issue. PERAA rearranges organizational boxes and consolidates authority but the public may have difficulty holding its elected officials accountable because all information about their performance self-released. In addition, a measure of accountability for education is removed under the proposed changes because the Mayor is in charge of both operations and oversight at the same time.

The following illustrations depict the local governance structures for Boston, Chicago, and New York City. The District of Columbia’s modified structure is illustrated in Figure 1 for comparison.

| Boston, MA | Chicago, IL | New York, NY | Washington, DC | |

| State Board of Education | Sets state-wide policy. | Sets state-wide policy. | Sets state-wide policy. | Has advisory and approval authority. |

| Mayor | Has overall fiscal and political responsibility. Appoints school committee and submits budget. | Appoints Board of Education and CEO. | Has overall fiscal and political responsibility. Appoints Panel for Education Policy and submits budget. | Has overall fiscal and (arguably) political responsibility Appoints 4 members of the State Board of Education (until 2009 when all are elected). Appoints Chancellor. |

| Deputy Mayor for Education | N/A | N/A | Oversees and coordinates the operations of the Department of Education, School Construction Authority, City University of New York, and Department of Youth and Community Development. | Oversees and coordinates the operations of public education, including development and support of programs to improve service delivery. |

| Local Department of Education | N/A | N/A | Sets local policy, provides system-wide services to accomplish goals. | Led by the Deputy Mayor for Education. |

| Local Board of Education | School Committee sets local policy. Has fiduciary and policy oversight authority. Hires and evaluates the Superintendent. | Sets local policy. Has fiduciary and policy oversight authority. Hires and evaluates the CEO. | Replaced by Panel for Education Policy with advisory and approval authority. | N/A |

| Superintendent | Develops, recommends, and implements strategies to meet educational goals. Recommends budget allocation. | CEO implements State and Local Board policy. |

Chancellor manages daily operation of school system, incl. local education policy. |

Chancellor manages daily operation of school system, incl. local education policy, but not facilities. |

| Ombudsman? | Yes, under Superintendent. | Yes, under CEO. | Yes, city-wide advocate under Mayor. | Yes, under Deputy Mayor for Education. |

| Independent Office of Facilities Management? | No. | No. | Yes. | Yes. |

| Local Education Entities | N/A | Provide site-based management of each school. | Has 32 Community Education Councils; each oversees a Community School District that includes public elementary, intermediate, and junior high schools. | N/A |

In this comparison, the District of Columbia has set a unique course of policy-making in public education. In Boston, Chicago, and New York, their respective state boards of education set policy for the state; the District of Columbia’s State Board of Education will not have this authority. Conversely, in Boston and Chicago, the local board of education sets policy while in New York, the locally-based “Panel for Education Policy” only has advisory and approval authority.

In many respects, the new governance structure within the District of Columbia is most similar to the New York City model, which includes a Deputy Mayor in charge of education, a Chancellor in charge of day-to-day operations of the school system, and an independent facilities management office. One major difference is that in New York City, the Community Education Councils are consulted on many important matters and provide an opportunity for the community input on educational issues. A second distinction is that the ombudsman is independent of the school system and serves as an advocate for the entire city.

Community input, and to a lesser extent, the idea of participatory governance, is a valued commodity and has played a substantial role in education reform in the District of Columbia. The Council and a plurality of stakeholders and community organizations have been persistent in requesting community participation, as demonstrated through input opportunities at Council hearings, public roundtables, and town halls. Effective participation by all stakeholders has come to be viewed as a necessary condition for promoting good governance. As the only independent body involved in the District’s public education system, the Council can play a central role in providing a reliable conduit for community input in addition to the difficult task of modulating messages and dealing with various stakeholders and interest groups.

Currently, three formal methods of community input exist. For state-level issues, the State Board of Education hosts monthly meetings and permits public witnesses to testify. Likewise, for statutory and oversight concerns, the Council invites the public to testify at hearings. Lastly, the Ombudsman serves as a vehicle for citizens to communicate their complaints and concerns regarding public education through. Nonetheless, the modified governance structure remains unclear about the vehicles for community input and voter involvement. An extension of the previous discussion of “citizen councils” and their potential impact, there is no uniform method of community input and most of the alternative routes lead to the executive branch rather than the Council, the only independent oversight body.

Currently, the routes for community input and involvement in education matters include:

This confusion and complication can be counteracted and remedied. Some theorize that effective participation is dependent on overcoming distinct but inter-related gaps.52 First, a capacity gap arises from the fact that meaningful participation requires certain skills or knowledge that the traditionally disadvantaged and marginalized segments of the District of Columbia do not typically possess. Further, participation is not costless and most people will not actively participate unless they perceive the potential gains to be large enough to outweigh the costs. Finally, a power gap exists where it is very likely that dominant groups may use participation to further their own ends. Participation is likely to be unequal, with members of dominant groups wielding superior power to further their own narrow interests. Theory and practice suggest a number of ways in which this countervailing power can be created.